- Them Bones.

I’m easily intrigued by the morbid experiences that history has to offer, so of course, I couldn’t resist the opportunity to visit what the website in Rome calls a “Bone Church”. I was ready for bones, and lots of them. I imagined a place similar to the crypts in Paris, where the walls are made of tibulae and fibulae and more skulls than you’d think could be shoved in an underground tunnel in a million years. The Capuchin museum in Rome was a slightly different experience, however. I can honestly call the formations of bones beautiful. We weren’t allowed to take pictures, but I distinctly remember several of the formations, with thin bones and what looked like hip bones (I should have taken an anatomy course before going) arranged to look like flowers. And they were remarkably delicate. The arrangements were all around and above us, mimicking light fixtures and scenes with full bodies which were re-assembled to appear as if they were walking towards us (while still wearing their habits!). They were also arranged geometrically like an hourglass and other religious symbols.

The 17th century Santa Maria dela Concezione dei Cappuccini church in Rome, Italy, houses the Capuchin Crypt and is home to over 3,700 bodies of Capuchin friars. Let me tell you a little bit about the Capuchins, because they are still relevant religiously today as they do much humanitarian work all around the world. The Capuchins are a Catholic order which was named after the their hats which had pointed brown hoods (cappa in Italian), which were marks of hermitage in Italy. For you coffee lovers, it is thought that Cappucinos are named due to a similar brown color. For you monkey lovers, the Capuchin monkey is named after the shade of brown. They are an offshoot of the Franciscans, founded in the 16th century. Their ideology involved intense poverty—the monasteries could possess nothing, and everything was to be obtained through begging. The friars went barefoot. The communities were extremely small. Eventually they spread out across Italy during the 17th century, and they also went on missions to America, Asia, and Africa. Nowadays, the missionary work continues and there are at least 200 missionary stations across the world.

Atop the site is a multimedia museum paying homage to several notable friars and their culture. Another point of interest is that the museum usually hangs the Caravaggio work Saint Francis in Meditation—unfortunately, the piece was on loan when we visited. There were numerous pieces of material evidence, though. It felt much like an archaeological museum.

I’ll leave this section with a macabre quote from the chapel: “What you are now, we used to be. What we are now, you will be.”

- Space Invader in Rome? Yeah, we were sketched out but there was plenty of “art”.

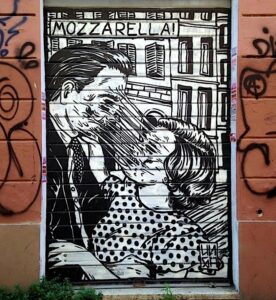

On our second day in Rome, we found ourselves far away from the tourist attractions in a neighborhood called San Lorenzo, which barely had a single square foot untouched by graffiti. Some of it was just words in spray paint, but other parts were images with great detail. It was a big change from the Colosseum and the Palatine Hill, that’s for sure. I appreciated the opportunity to see a piece of “real” Rome before we had to leave. The San Lorenzo area housed urban development worked in the late 20th century, and the area was victim to many bombings during WWII. Some notable street artists who’ve left their marks are Alicé Pasquini (a Roman artist, street and otherwise, and uses found materials in urban settings), C215 (a French street artist who has been referred to as “France’s answer to Banksy”), and Borondo (a Spanish muralist). More include Clemes Behr, Herbert Baglione, and MOMO. I’m fairly certain that I spotted a small tile left behind by Space Invader (another French street artist known for his work based upon old video game characters). It is a site of many international and national artists. Rome seems to be accepting the street art in stride (as if they needed another claim to fame!) as they released a map of Street Art in Rome. An interesting blurb was delivered along with the itinerary: “Change perspective. The Street is your new Museum.”. I wonder what the street artists themselves would feel about the framing of their work in such a sway, as many might be contrary to the institution of museums? The map does not linger in certain neighborhoods very long—it spans across thirteen of the fifteen municipalities of Rome. Had I had more time, I suspect that following such a guide might have been a much more valuable view of modern Rome, taking me through many different types of neighborhoods. This has inspired me to seek out a Street Art tour whilst we’re in Cologne.

Here are a few smaller pieces that I could snap pics of as we were walking.

Here are better pictures by people on the hunt for street art:

Sources:

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Capuchins“. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge

University Press.

Colavolpe, Camilla. “Top 10 Places To Admire Street Art In Rome.” Culture Trip. February 19,

- Accessed July 10, 2017. https://theculturetrip.com/europe/italy/articles/top-10-

places-to-admire-street-art-in-rome/.

Hana. “Museum and Crypt of the Capuchin Friars.” Romeing | Rome’s english magazine, events

and exhibitions in Rome. June 16, 2017. Accessed July 10, 2017.

http://www.romeing.it/museum-and-crypt-of-the-capuchin-friars-rome/.

Shirazi. R. “Street Art In Rome.” Features, Other attractions, Things to See in Rome, Hot Topics.

November 14, 2016. Accessed July 10, 2017. http://www.romeing.it/street-art-in-rome/

Lillie ,

I appreciate your question about the framing of graffiti as Art with a capital ‘A.’ I too wonder what a street artist would think about being institutionalized in such a way. This idea of institutionalization makes me think of the acceptance of the historical avant-garde by the art world over the last 100 years, and I think there are clear similarities between these two situations.

Dada artists wanted to destroy the institution of art: museums, galleries, all of it. In response, the institution absorbed them, possible as an act of self-defense.

The fact that the city has begun creating street art pamphlets and tours interests me greatly, and I see this as a similar act of institutional self-defense. Street art is as much of an indexical mark as it is a visual composition. Graffiti is a record of an artist’s defiance, his civil disobedience, as well as an aesthetic composition. What defense does the institution of a city have against this type of subversion? They promote it so that act of creating street art is no longer subversive, at which point it loses at least half of its meaning as a subversive act.

I do not think street artists would be pleased about the tours.